Nashville Film Festival: Day One

Special from “Our Man in Nashville”, Jason T. Sparks

Nashville, Tennessee, 10 May, 2018: The Regal Hollywood 27. This theatre is next to a building known as 100 Oaks, which was in the 1950s the first of a new, dynamic concept in architecture and commerce known as a shopping mall to be built in Nashville. It died in the early nineties, was revived in the late nineties, died again in the early ‘aughts, and now survives as a phalanx of medical offices for Vanderbilt University. (For the most part, anyway; these are probably the only doctor’s offices in the world to share space with a Burlington Coat Factory, which is a holdout from the original iteration, and somehow never died. True story)

Next to that mall stood, for many years, The Martin Twin, the theatre you have in your mind if you’re of a certain age: NOW SHOWING in black letters, brown curtains over the walls, popcorn in the red box, the little fellow on it proclaiming “Popped Fresh and Hot—JUST FOR YOU!” In 1975, that theater hosted the gala premiere of Robert Altman’s Nashville.

Decades later, it was torn down without ceremony; in the immortal words of Hyman Roth, there isn’t even a plaque.

There is, however, this theatre, a nicer-than-average multiplex bedecked in neon that tries and succeeds to recapture Art Deco, and tonight, it’s playing host to the Nashville Film Festival. For the NFF in general, this is year 49; for my involvement in any way, shape, or form, this is year one. As my Lyft driver lets me out at the door, a euphoria hits me: this is actually happening, and I’m part of it. Event staffers smile warmly as they acknowledge me. The box office/Will Call stand has a laminated PRESS pass for…me. A red carpet leading into a VIP area (read: a bar), on which people are standing and being photographed, is perilously close to…me. I don my laminate, grab my envelope full of tickets and my complimentary copy of Variety (Ooooooh! The magazine for Hollywood bigshots? I can haz?) and walk in. The gal who tears your ticket in half as you enter modern theaters takes one look at my press pass, smiles from ear to ear, and says “right this way, sir” as she waves me in. I got a wave-in! I begin to think like Snoopy: here’s the world famous film critic walking the parapet. Ah, Jean-Luc, Orson, Akira! How’s tricks, boys?

Knowing I need to, I set about composing myself; we’re here, after all, to write reviews, to be detached, cerebral. I’m able to maintain that façade for a few minutes, before finding myself in the presence of…a celebrity. Actually, I’m facing the one thing better than a celebrity—a local celebrity. Although he retired over a decade ago, I immediately recognize one Chris Clark, the news anchor at Nashville’s CBS affiliate from slightly before my birth up to my late thirties. (He started at the CBS affiliate for Atlanta; born Chris Botsaris, he was given a markedly less Greek name so he would not be too terribly different from his rival at the NBC affiliate, whose name was also simple—Tom Brokaw.) I do not lose my composure, instead channeling my amazement into a text to my wife:

“OMG CHRIS CLARK IS TOTALLY HERE WATCHING THE SAME MOVIE”

I find my place in the theatre, take stock of all the ponderous swag I’ve been handed, find homes for all of it in my backpack, pull my smallest notebook from one of the pockets. In it, I put down the names of PR firms sponsoring the festival, as those names fill the screen: while visions of copy writing gigs danced through his head. The lights dim.

The first fIlm on my agenda is Television Pioneer: The Story of Ross Bagwell, Sr, a by-the-numbers documentary about a native of Knoxville, TN who, upon seeing a television for the first time in 1951, realizes that this new medium is his future, and he sets about making it so. He heads to New York, where he parlays a gig as an NBC page into full-time employment with the network. From here, he heads to Canada, where he produces for NBC and CBC, and then goes…back to Knoxville. Ensconced again in East Tennessee, he opens an advertising agency, which eventually becomes a video production company whose forte is sitcoms, made quickly and cheaply. He creates content for The Nashville Network and Nickelodeon, and eventually produces most of the content for HGTV, who eventually move to Knoxville–and buy Bagwell out. HGTV is then bought by Discovery Communications, purveyor of 600-lb lovers, households overflowing with children, and other modern freak-show tents; subsequently, Discovery, a massive, global player in communications, moves its headquarters to…Knoxville.

Looking at the film as an essay, the thesis of which is that Ross Bagwell was a game-changer who made his hometown an unlikely hub for an industry still based in larger, more cosmopolitan towns, it works. We get ample support for that claim. The support, however, is never surprising. There’s archival footage of Bagwell’s work, and there are talking heads, nearly all of whom are Bagwell’s own family (all of whom, to be fair, worked in some capacity for Ross). This is not a challenging documentary, so much as a cozy documentary, if you can imagine such a thing. It’s a love letter to a patriarch. Not an undeserved letter, understand, but a love letter nonetheless. For those seeking to learn about the guy, it delivers. For those seeking anything else, well…seek elsewhere.

After learning about Mr. Bagwell, my second/final film for day one was Prototype. You may recall that, in my sneak preview, I shared the exact words from the PR copy–“As the deadliest natural disaster in US history strikes Galveston, Texas, taking an estimated 6,000 to 12,000 lives, a mysterious televisual device projects images of unknown origin.”

Before I go any further, I feel the need to tell a story from my childhood. When I was about ten, my grandmother and I went to the Woolworth’s in downtown Nashville, where I bought a 45 of Thomas Dolby’s “She Blinded Me With Science.” Then, upon returning to my grandmother’s house, I played it for her. Her response: “Well, Jake, that was…right interesting”. As an adult, I have realized what she was really saying—this isn’t Glenn Miller, and I can’t even with it, but no way am I about to hurt my grandson’s feelings, so…

I bring this up because Prototype was, as I soon learned, part of the NFFs “Graveyard Shift” collection, curated by local critic Jason Shawhan, and as such, it was an experimental film. I had expected it to be a straightforward narrative, maybe with a sci-fi flavor. What the film actually turned out to be was…right interesting.

The natural disaster in question is the hurricane which struck Galveston in 1900, and we are introduced to it through stereoscope pictures of the storm’s aftermath—which makes the option to shoot in 3-D all the more contextual, as stereoscopes (think ViewMaster, v 1.0) were 3-D photographs available in the early 1900s. We are then subjected to footage of tidal waves for several minutes. I say subjected to because, in addition to being 3-D, they are (the audience decided in discussion after) also upside-down, which is highly jarring (and may be how such a wave looks to someone about to be hit by it).

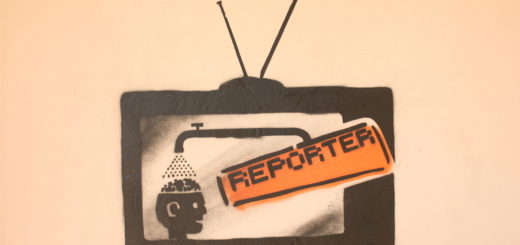

Then, suddenly, with no explanation, the televisual devices appear. They are squat, oblong TV sets from the 50s, and they appear by means of a jump cut away from the waves to them. When first seen, they glow an angry white, then begin to project images…of something. Several somethings, actually, and none of us watching were ever sure of what. Modern Galveston? Modern cars? Flowers? Statues? And these images are being shown to whom? People in Galveston in 1900? Us, now?

As the film went between the hurricane and the televisual devices, found myself alternately wanting to leave the theatre, scream, and/or pass out; I also suspected I was entering a hypnotic trance. If their is such a thing as MK-ULTRA, the CIA mind control experiment so often discussed by the tinfoil-hat crowd, Prototype is part of it. I came away amazed if confused. My exact words to Shawhan were, “well, I was expecting something totally different, but, if I had known what it was going to be, I would not be about to spend all night parsing it”. The Bagwell film was cozy. This was not.

Up next: Day Two—walking through NYC, hero’s journey through Niger