Black Like Me, Part II, Hollywood Strikes Back: The Problems of Nostalgia and Colonial Revisionism in “The Legend of Tarzan”

Thanks to @lordbyron080808 for taking a look at a new film from his unique perspective!

Last month I reviewed the Matthew McConnaughey Civil War drama, “Free State of Jones,” and I tried to convince readers that, despite its dryly academic, anti-Hollywood, and dramatically threadbare presentation, it remains a film worthy of your spending eight hard-earned dollars to see it. That was hard.

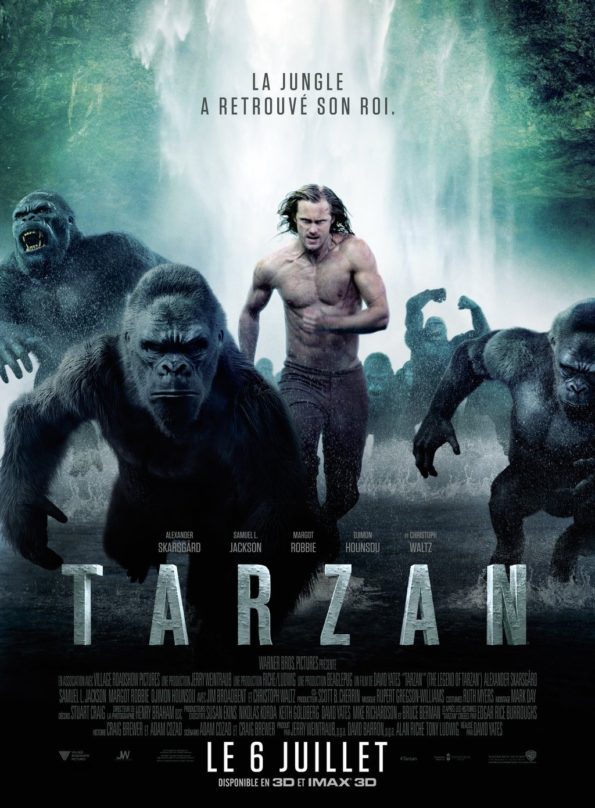

This week I have assumed an even more Herculean task: to convince you that, despite its very attractive main characters—I’m still uncertain who is more attractive, Alexander Skarsgård’s muscularly loin-clothed, but visibly scarred, “Tarzan,’ or Margot Robbie’s, effervescent, but always modestly-clad, “Jane”– its charming Samuel L. Jackson-inspired Everyman appeal, its slick, very “Hollywood” production values, and its ingeniously taut and well-written dramatic presentation, there still remains something almost inchoately disturbing about this film that peeks out only after you’ve had time to process the blockbustery thrill ride that is “The Legend of Tarzan.”

For the film is a cinematically beautiful and generally well-made movie which rehashes and skillfully adapts much from the first two Edgar Rice Burroughs’ novels in his “Tarzan” series: “Tarzan of the Apes” (1912) and “The Return of Tarzan” (1913). Unlike the novels, which see Tarzan born in 1889, and most of its principal events occurring twenty years later in the 1910s, the movie displaces the setting to the late 1880s, and its dramatic action centers around the personal, social and political aftermath of the 1884-1885 Berlin Conference, wherein the various European powers agree to partition central and Southern Africa according to their own interests and irrespective of the various linguistic, cultural, or tribal distinctions of the Africans themselves, a partition which would lead to the “Scramble for Africa” by the various European powers.

Thus, the movie, to its credit, quite openly deals with the over-sized “C”-worded elephant that invariably trammels underfoot everything in the space that Tarzan occupies: that of the historical problem of the European colonization and exploitation of Africa in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The film’s plot commences about a decade after the events of Burroughs’s first novel, which narrated the strange circumstances of how his parents arrived in Africa, his strange birth and upbringing by a tribe of apes, the killing of his ape-mother, Kala, by a hostile tribesman, Tarzan’s ferocious revenge, and finally, his meeting and dramatic rescue of the daughter of an American missionary from a vengeful ape attack.

In the movie, all these events are recounted in nostalgically, and thus, somewhat historically untrustworthy, autobiographical flashback narratives by Tarzan to his American traveling companion, George Washington Williams (Samuel L. Jackson,) or by Jane to Williams or more often to, Léon Rom (Christoph Waltz,) a merciless Belgian mercenary who captures her and her African friends, thus setting up the film’s central rescue drama. All of these flashbacks are intended either to stimulate their on-screen auditors into sympathetic assent to the urgency of their reckless mission of rescue or to inspire foreboding terror of what the wild man is capable.

Thus, while these flashbacks serve the dramaturgical purpose of educating the viewer of the heroic and romantic backstories underpinning the actions actively narrated, they also serve to idealize the couple and their history.

That the couple is neither as romantically stable nor as heroic as these narratives insist represents a central, if somewhat hidden, motif that occurs at a number of critical moments in the film: this motif first appears at the beginning, when Tarzan, who has returned to his ancestral home in England and re-assumed his English birth name and status of John Clayton III, Lord of Greystoke. Here, he is openly unhappy, although we are not told why.

Soon thereafter the unnamed British Prime Minister (Jim Broadbent) arrives to sow even greater unrest in the Clayton household by forwarding a request from the Belgian King, Leopold II, to Clayton to visit and inspect his personal African colony in the Belgian Congo. He initially declines the invitation, refusing to once again put himself and his wife in danger by returning to a region where the African tribal leader, Chief Mbonga, has vowed to avenge himself of Tarzan’s earlier murder of his young son. He eventually relents, at first conditionally, when Williams, an American diplomatic envoy, intervenes in the discussion, ironically challenging the stories of Clayton’s legendary exploits as Tarzan, and his love of the beautiful American, Jane. Williams even sarcastically cites the famous “me Tarzan, you Jane” line made famous by Johnny Weismeuller in a 1932 off-screen interview, but which many viewers have assumed to appear on-screen. (In Burroughs’s original work, Tarzan is fluent in several languages, including English.)

Thus challenged, (and secretly humiliated,) he gives way, and agrees to accompany Williams to the Congo, (who wishes to verify his suspicions that Leopold is clandestinely engaged in the illegal enslavement and brutal oppression of the native tribes) so long as Jane remains safely in England. Soon, however, he acquiesces to her wish to accompany them when she reminds him that Africa is her home as well, and that returning there might make the both of them happier.

And so, they travel to Africa. But instead of following their official itinerary, the group jumps ship to visit the small village where Jane’s father worked as a missionary, and she grew up. This homecoming, initially, seems joyous, until, after one of the young tribal girls gives birth, one of Jane’s childhood friends innocently asks her whether she has children back in England. Jane is clearly troubled and (similar to Tarzan earlier when questioned by Williams earlier) secretly humiliated by her and her husband’s infertility.

Perhaps to bolster her own flagging sense of marital bliss, later that evening, she initiates the pattern of romanticized flashback narration that connects the film to Tarzan’s mythic past by explaining to Williams, who is a new traveler to Africa, (and thus, the audience’s representative in the movie) how Tarzan was initially regarded as an evil jungle spirit by many of the local tribes, and how she and Tarzan met, and how he saved her by shielding her from a brutal ape attack, and how they fell in love as she helped him recuperate from his subsequent injuries.

And while she doesn’t draw much attention to this fact in her narrative, her story clearly demonstrates a repeated pattern in Tarzan’s “mythic” history—that while he survives the various dangerous encounters that confront him, Tarzan, typically seems to lose nearly every one of them. Although he saved Jane from a worse fate, his fellow Mangani apes beat him to within an inch of his life. A close look at Tarzan’s body—an act many lusty hetero female and gay male viewers would certainly approve—gives evidence that he has had a number of such losses in his past.

This losing streak continues into the movie’s present when, soon thereafter, the village is attacked by Rom and a party of mercenaries, who inflict serious damage and flee with a number of hostages, including Jane, aboard their steamboat. Tarzan, himself, narrowly avoids death and capture as the boat pulls away.

This pattern of defeat, but survival, is constantly repeated throughout the movie, with one notable exception. This exception is critical to the storyline, however, even this victory does not redound to Tarzan’s credit. For it calls into question the supposed “benevolence” of his, and by extension, all white men’s, presence in Africa. Moreover, this exception forces both Tarzan, and us, as viewers to admit without equivocation to the injustice of our treatment of Africans. And in an era of “Black Lives Matter,” such a question, when left unanswered, stands as a damning indictment of the “white man’s justice.”

At this point, the viewer realizes, in a flash, that not only have we been led, by the couple (and filmmaker’s) desperate nostalgia, to misconstrue important facts about nineteenth century African history, we realize that the African descriptions of Tarzan as “an evil jungle spirit,” when not filtered through of the Western lens which regards African folklore as “silly” animistic superstition, is essentially true. Moreover, we finally recognize that, the only reason that we didn’t credit this description previously is because they are Africans, while Tarzan (and Jane,) primarily because of their whiteness, are regarded as more credible historical narrators.

Thus, this movie, which on its surface seems to champion a narrative of historical nostalgia vis-à-vis the openly brutal and oppressive era of the late nineteenth/early twentieth century European colonization of Africa (the era in which the Tarzan novels are set,) which argues that, if only the whites of this era could have treated the Africans as they did a generation earlier, then perhaps the relationship between Blacks and whites might be better than it is, ultimately upends this Romantic and nostalgic conceit. For, a close reading of the movie shows that this r/Romantic reading (both romantic and Romantic) are fictive (and ultimately racist and infertile) constructions that conceal historical truths and render everyone either embittered or unhappy.

The veil of nostalgia and historical revisionism has been lifted, it seems. The problem still remains of how to be happy in its aftermath. This movie appears to say, confront the truth and you will eventually be happier. I’m uncertain if that’s enough, but it is a start.

@lordbyron080808 is graduate of The University of Texas-Austin with advanced studies in French and English literature. He lives in Austin and enjoys reading, discussing history and current events.